CULTURAL COMPLEX AND THE ELABORATION OF TRAUMA FROM SLAVERY

Denise G. Ramos

The idea of studying slavery from the psychological point of view occurred to me while I was giving a word-association test to a group of students in an analytical psychology workshop. To my surprise, one of the students said that he was very sad when he realized that he had associated the word "ship" to "black ship".

"Black ship" was the name given to the vessels that brought Africans to Brazil to be sold as slaves. Later I found out that other students in this city had had similar reactions. I was working in the city of Salvador, the former capital of Brazil, in the state of Bahia, located in the north-east of Brazil, with a population of 80% African descendants. These students were doctors and psychologists, and it would be nearly impossible, just from their appearance, to tell which of them were of African descent.

We were in 2006, 118 years after the abolition of slavery in Brazil, so some of these students could have had relatives, grandparents or great-grandparents who had been slaves. The test revealed a conflictive and traumatic situation in the personal and collective unconsciousness. The kidnapping, breaking of family bonds, compulsory migration, the terrible journeys in the black ships, the submission and degrading situations, such as being sold, and all the mistreatment that Africans were submitted to, undoubtedly created a highly traumatic situation. According to historians, during this journey, a third of the African slaves died; the most common disease was Bantu, which means to miss someone. This level of mortality in black ships was three to four times higher than among free immigrants (Eltis 2003).

Of the total of 11 million Africans that were enslaved, three million six hundred thousand are estimated to have been brought to Brazil. Today, 51% of the Brazilian population comes from African origin. In the last few years a significant amount of literature has dealt with the history of these people, their rebellions and struggles to build an identity. However, from the psychological point of view much remains to be done.

One of the main questions for us today is how the descendants of these slaves are living now and how they still cope with these traumatic events.

One hundred and twenty-two years after abolition, Brazil remains a country marked by racial inequality. Statistics show that in Brazil the majority of people who are unemployed, uneducated and poor - as well as felons in jail - are of African descent (Henriques 2001; Kilsztajn et al.2008). Studies show that up until the first half of the 20th century, during the process of generalization of free labor and competition, the great mass of descendants of the old slave population lived in economic marginality (Furtado 2000; Hoffmann 2001). Brazilians themselves often attribute this to the legacy of slavery, arguing that the experience of bondage crippled Afro-Brazilians so severely as a social group that they proved unable, one century after emancipation, to compete effectively against whites for jobs, education, housing, and other social goods.

Clearly, the legacy of slavery helped shape this process by producing both employers unaccustomed and unwilling to bargain with their former slaves, and a former slave population with very specific demands concerning the conditions under which they would work as free men and women. That legacy is present throughout most of Brazil, where white immigrants are clearly the 'winners' and blacks the 'losers' in the process of economic development and prosperity. Moreover, while European descendants often take pride in their ancestors' history by traveling to their family's place of origin, and taking great pleasure in telling and retelling how their grandparents crossed the ocean and managed to be very successful in the new land, I observed that African descendants practically never touch on this subject.

Recent conducted among graduate students in the cities of Salvador and São Paulo confirmed this fact (Ramos, 2009). It should be remembered that São Paulo, a highly industrialized and developed city located in the South of Brazil, was basically formed by European immigrants, mostly Italians, Spaniards and Portuguese. The majority of its population is white and the influence of European culture is significantly present in its architecture, education, and local habits and culture. The two groups were compared as to their feelings with regard to their ancestors. The response to the questionnaire verified that there is a significant difference between the descendants of Europeans and Africans. While the former are familiar with the origin of their ancestors, what country their grandparents and great-grandparents came from, and expressed a desire to visit that place, the descendants of Africans say they do not know the origin of their grandparents (the majority does not even mention the city where these grandparents lived) and left blank the question on whether they would like to know their family's origin. To the question on the influence of the color of skin in social and work relations, all the whites answered that their appearance is a helpful factor, whereas the black residents of São Paulo considered their color as a factor that generates feelings of inferiority and discrimination. Within this group we observe conflicting sentiments: many answer that they are proud of their origin but are ashamed of their parents and feel inferior.

Another study of this project observed and compared white and black students in a school of the city of São Paulo - age between 12 and 18 years. Ten hypotheses were raised to verify and compare self-esteem, whitening, racial identification, attributes of beauty, wealth, social and professional success. We used as instruments the scale of self-esteem of Rosenberg (Avanci, J.et al. 2007) and two questionnaires. In one of them the students had to choose which one of the four pictures (2 whites and 2 blacks) corresponded to a quality. For example: which one of them is more beautiful?

The results show that the vast majority of black teenagers assigns to the whites greater wealth, beauty and professional success. However, the black female students believe that they could also have professional success. Probably this is due to popularity of black artists and models and great appreciation of "black beauty" in some cultural circuits. Interesting to note is that black students see themselves as having so many friends as the white ones, revealing the same level of sociability.

Here we may reason that when a black teenager says that the blacks are uglier, poorer and with less possibility of success he or she is in a death end street. Feeling trapped in an undesirable body, the shadow (in this case, the good qualities) is projected into the white colleagues. A natural consequence is that there was a unanimous desire to look white. In our research, most teenagers of both sexes see themselves whiter than they are and declare that they would like to be white. Similar results were found by Lima and Vala (2004). In their study they investigated the effects of perceived skin color and of social success on the whitening and on the infra-humanization. The found out that blacks that obtain social success are perceived as whitener than the blacks that fail. A mediation analysis indicated that as much the blacks with success are whitened, more typically human characteristics are attributed to them. These surveys confirm other studies that reveal a whitening desire and the association of blackness with inferiority. Walter and Paula Boechat in their paper "Race, racism and inter racism in Brazil: clinical and cultural perspectives" say: "the basic, distinctive character of Brazilian racism is that it is based on the color of skin. This turn racism into a central element in the collective shadow of Brazil" (Boechat,W and Boechat, P. 2009, p. 196)

The skin color does not allow secrets, forgiveness or easy scape. It obliges the individual to identify with a group with whom he or she may not want to belong. There is no choice. As Kaplinsky says "skin color could trigger emotional reaction and is a key to the cultural complex" (Kaplinsky 2009, p.64).

The results of these researches as of many others point to a possible psychological cause for the socio-economic distortions described above and raise the following questions:

Could it be that the self-esteem of African descendants became so low that this has made their social ascension difficult? What would be causing these symptoms? Would they be related to an underlined collective and cultural complex? Could slavery traumatic events be the core of this complex? Or could the slavery traumatic situation be fixed in a cultural complex that is transmitted from generation to generation?

In this paper I will make a brief analysis of trauma and cultural complexes and how these may manifest in a segment of African descendants living in a specific region of Brazil. Without trying to reduce this complex phenomenon to a single psychological cause, I will explore symptoms of a possible cultural complex and a collective trauma brought on by slavery.

The historical center of the city of Salvador, Bahia (the same city where I gave the workshop) was chosen for this study. The city of Salvador ("Savior") is of great importance to this study, for this was the place where many "black ships" arrived and where slaves were sold. It has a very well conserved historical center, where many 18th century houses are still preserved, as well as the sites where slaves worked and lived. Over time, after the abolition of slavery this section of the city underwent a major transformation and was named a world cultural monument by UNESCO in 1985 (Cerqueira 1994; Miranda and Santos 2002).

The name of this historical center is very significant: "Pelourinho", which means pillory or whipping post, a place where the slaves were sold, tortured and often killed.

THE SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGICAL RESEARCH

The research was carried out between 2005 and 2009 and was centered in:

• A. Historical documents

• B. Field observation- what happens on the streets

• C. Visit to museums and art galleries in the Pillory and interviews with six painters

• D. Trip to the center of two of the most famous musical groups of the Pillory

• E. Visit to black sacred places

• F. Interviews with community leaders

A. Historical Documents

Locations of the pillory

Originally the pillory was placed in the city's first open market, the "Praça da Feira" which today is known as "Praça Municipal" (Municipal Square), an open square at the top of the hill, just above the place where the "black ships" arrived. Today, there is a modern and colorful fountain in its place.

Sometime between 1602 and 1607 the pillory was moved by the governor's decree to the "Terreiro de Jesus" (The Jesus Yard), a place "far away from the public eyes". But The Jesus Yard was the site of the Jesuit church and school, and the screams and groans interfered with church services and teaching. Today, in the same place as the pillory, stands a statue of French origin of Ceres, goddess of fertility and agriculture.

So by request of the priests, it was removed again, this time to the bottom of the "Porta de São Bento" where the "Praça Castro Alves" (Castro Alves Square) is now located. The pillory was removed for the last time in 1807, and taken to the square which would come to bear its name. So Salvador's pillory last stood at the top of the sloping "Largo do Pelourinho" (Pillory Square), the final stage in its journey, and it would stand there for another 28 years, until 1835. Today this is the main place for musical events to take place. The neighboring slave-auction site was renovated and converted into a museum (Rocha 1994).

The building of water fountains, the monument to the goddess Ceres, and finally a place for musical events where formerly stood the pillory may be interpreted here as an attempt to transform a spot associated with suffering and death into an area of joy and the celebration of life, even if for most of the population this is an unconscious act.

B. Field Observation- What happens on the streets

It is common to see women doing tererê, an African style of braiding hair, on tourists. Here there is an attitude of pride and valorization of a tradition in a culture where straight blonde hair is more appreciated. We also see women in African clothing selling traditional food and accessories made of beads and stones. African-Brazilian aesthetics has been gaining new elements through clothes, accessories, hairdos and prints.

Recently "ethnic toys" have been appearing in the market, such as black dolls dressed as Africans. Questioned about the ugliness of the white doll, the black seller smiling responded to me: "but that's the idea. See if you understand". (Figure 1)Besides the ethnic dresses, there are many stores that sell African–Brazilian music as well as African musical instruments.

Scenes of people performing the capoeira, a mixture of dance and fight, are also a common sight in the Pillory. Many times I ran into groups of people performing this art. The capoeira is considered a movement of the resilience of black culture and today is taught in schools all over Brazil, as well as abroad. According to Carlos S. Paulo (personal communication, April 2008), the capoeira was born of the necessity to develop a physical intelligence in people whose bodies were chained and oppressed. Thus the movements express the fight and defense against the oppressor, but they needed to be disguised as a form of dance so as not to appear as a threat to their lords and masters.

We can see here that some African traditions are not only recollected and represented but are also recalled and imagined, through association with dance and artifacts, some of which have been arranged and designated for that purpose. Here, the "power of telling and looking" is intimately intertwined with gestures and associated with the capacity to see and the possibility of making things visible (Hale 1998). But, which things do they want to make visible? And what's invisible in that place?

Finally we had seen some children and teenagers walk the streets begging for money and white man and woman tourists in a very open sexual behaviors with the blacks.

c. Visit to art galleries in the Pillory and interviews with six painters

Thirty-one cataloged art galleries were visited (seventy percent), where the most common themes among the paintings were noted and images looked for that had some reference to the local population and/or reflected slavery. The main themes found in paintings were:

Nature: with young Indians and wild animals, especially birds and jaguars.

Human figures: paintings of sensual, young black women, mainly just the face, always in African clothing. While the women look joyful, a possible representation of the African anima, the few paintings of men reveal a deep sadness and are somber in tone. In this case, the painters were all men. (Figure 2)

There were only three paintings with references to African origin: just one with slaves. In the other two, the natives had their eyes closed. What don't they want to see? The representation of human figures with eyes closed is present in great number of paintings, especially when there is a picture of white man in the center. However, when the frame depicts only afro-descendants the black figures keep their eyes open. Are we watching a difficulty to face the white man? Are we dealing here with conflictive feelings? What is so difficult to be aware? (Figure 3)

Another very interesting painting depicts a woman with a sad look watching a bird nest. One bird carries a book and the other a pencil. In nest there are also two pencils. According to the author, the massage is that the way to freedom is through education; the people can only evolve when they know how to use pencil and paper (Raimundo Bastos dos Santos personal communication, 2009). Yet according with the same painter, another path would be football and he pictured two children football players carrying eggs instead of balls in a nest of birds. (Figure 4)

Scenes from the past, portraying the activities that took place in the Pillory, probably from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th, without any reference to slavery, torture or submission. There were not figures of the present time. The reference is mostly of an imaginary peaceful, non-conflictive past. We see also scenes of people dancing the capoeira and playing musical instruments. However, the most common paintings are those that represent the Orixás, gods of the African-Brazilian religion called Candomblé. These are strong and joyful figures generally portrayed dancing and dressed in very colorful clothes and accessories. (Figure 5) Here we observe perhaps a point of pride and self-esteem, for the priests of the African religions are highly respected and consulted by politicians and prominent people in Brazil. In terms of religion, it is important to that most Brazilian religion beliefs, besides Christianity, derive from African myths and legends, and the language used in these religions has been passed down through generations. The mythical aspects of these beliefs have influenced the cultural development of the country.

D. Visit to the center of two of the most famous musical groups of the Pillory: "Children of Gandhi" and "Olodum"

The group "Children of Gandhi", with approximately 10,000 members, started as a cultural and musical (Carnival) organization whose aim was to preach peace in honor of the Indian leader Gandhi. They cultivate mystical-religious African-Brazilian traditions and their costumes are white and blue to represent the peace proposed by the Mahatma. Their songs make references to the beauty and strength of the suffering black people who, although marginalized and discriminated against, still demonstrate their art, their joy and their legacy from the land of their ancestors (old Africa).

The other group is called Olodum that means "God of the gods", God creator of the universe. While most Brazilian musical groups wear yellow and green, the group Olodum adds red and black to their costumes. According to them, red stands for blood and black for the pride of their race. The rhythm is strong, the attitude a mix of fun and aggressiveness, and the loud sound of the drums, they say, "keeps the ghosts away". The songs are usually about the creation of the universe, the wonders of the creator and the origin of the slave race. In one of their most popular songs they say they were born in Egypt and are sons of the pharaoh. Here we see a fantasy of grandiosity, since no slaves were sent from Egypt to Brazil.

In the quest for an identity, it is only natural that we should seek our myths of origin. In the case of African descendants, this return to the past touches on the question of the African Diaspora, since along the way, many lost their parents' background, history and place of birth. Thus the music, the dresses and accessories create an image of "Mamma Africa", idealizing a mythical Africa in order to be able to create African-Brazilian traditions. On the other hand, some of Olodum's lyrics are famous for the joyful rhythm that expresses hope in the construction of a united country. In these songs there are no references to slavery, in fact, one of the most common themes is the black hero that shakes the country and transforms it, not with war but with an amorous attitude.

E. Visit to the church of Our Lady of the Rosario

Former slaves built this church in the 17th century and decorated it with the gold that they could hide in their pockets while building churches for their masters. Very well hidden in the rear there is a small cemetery and a kind of glass window. An excavation revealed that the skeletons buried there were of slaves still wearing their chains, slaves that were killed in the pillory. Their bodies had to stay exposed to the public so that they would serve as an example. However, during the night the members of the community would come and bury them in a hidden place. The small glass window has two statues of the slave Anastácia, who became one of the few myths of slavery. Anastácia is the legend of a beautiful young slave. She is desired by her master, whose wife is so envious of her beauty that she has Anastacia's mouth covered so that she will die of hunger and thirst. At the bottom, this legend praises the black beauty and sex appeal as superior the white woman's.

F. Interviews with business people and community leaders

There was a strong movement of transference and counter transference while doing the interviews. Sometimes the interviewers made me wait a long time. So they proportionated to me, perhaps in an unconscious way, the experience of lack of respect and humiliation. As I understood that it wasn't personal (my skin color didn't help), I hired an African descendent as my assistant.

The main observation among shopkeepers and some community leaders is that there is a deep concern with the commercial situation of the Pillory. The main problem, according to them, is that the residents of Salvador really only go to the city's historical center when there is a concert or event taking place, so many stores and restaurants have been forced to close their doors.

One particularly interesting interview was held with Mr. Clarindo Silva, who has been living in the Pillory for 50 years and owns the oldest and most famous restaurant, the "Cantina da Lua" (Tavern of the Moon). Mr. Silva is very proud of the Pillory and of his own history, and even showed me a suit in which he paraded in the Pillory fashion show. No doubt one of the leading defenders of the preservation of this site, Mr. Silva says that the Pillory should be a place with schools and drugstores and not only a historical place or an open-air museum, meaning that they cannot just play for tourists but must go on and change their history. I think that Mr. Silva is leaving in the present and probably had overcome the racial problem.

CONCLUSIONS

All these observations allow us to raise several questions. The first set of questions below is similar to those raised by Eyerman (2001) in his book Cultural Trauma: Slavery and the Formation of African American Identity when analyzing slavery in the United States:

What pictures should African-descendants present to themselves and to the tourists and the white population? How has the cultural expression of African descendants evolved, changed, and revolved back to its origins over generations?

The true history of the Pillory, as we see it, is hidden in a small cemetery behind a church and in the bitter speech of the Pillory's habitants. There is no conscious interaction between the cultural and symbolical richness and their daily life. Although African culture is deeply ingrained in Brazil - as can be seen in music, dance, food and religious practices - it seems that its acculturation remains restricted to these activities and is not integrated with others, such as profit-making economic activities. The buildings and houses are in need of better care and many residents are burdened by financial problems. It is clear that the inhabitants of the Pillory do not use their ability to show their many qualities and creativity, that is, to make their world visible (or invisible) as a form of power and part of the social construction of their identity.

Is the Pillory just an exhibition, a kind of theater that hides the true self of this population? Is the lack of representation of slavery a repression of the trauma or a form of resilience of this culture?

According to Singer and Kimbles' (2004:19) affirmation that a traumatized group may represent a "false self" to the world, we could say that the customs, the paintings and the dancing that we observed could be showing a "false self", and that the more authentic and vulnerable identity is hidden from the public eye. It is possible that such a traumatized group with their defenses may find themselves living with a history that spans several generations, several centuries, or even millennia with repetitive, wounding experiences that fix these patterns of behavior and emotion into what analytical psychologists have come to know as complexes. (Singer and Kimbles 2004:19)

The interviews with the artists and with important community figures, as well as the visit to the slave cemetery and the song's lyrics, reveal another side of suffering and trauma. Most songs refer to a fanciful and unreal past, with fantasies of power and grandiosity.

We can also note a certain depression on the part of the interviewees, for there is little perspective in the future and a sense of dismay. Were they the future of the black teenagers of our study?

The habitants of the Pillory expect help from the government and complain bitterly about the lack of official support. The painters don't feel recognized and valued and everyone seems worried about the possible depletion of their place. However, there is very little private initiative. We observed certain passivity and an almost childish resentment. As we know, people in whom the effects of trauma become ingrained often develop a chronic sense of helplessness and victimization, as we have seen in our study. So it becomes clear that behind the colorful paintings there is deep depression and sadness. Our data allow us to say that conflicts, suffering and aggressive energies are very seldom expressed. By the contrary, most of the images are soft and joyful, expressing an idealized nature or paradise.

Probably, the energy used in warding off the memory of the traumatic experience impoverished the mental life or the strength to take life in a more active and conscious way. Although the defenses helped to survive at the same time there are repressing the necessary energy that could broke the racial barrier.

While this Historical Center protects and gives a framework to its habitants, at same time it is a prison that forges an identity. An identity mainly based on skin color. The African descents may feel at home and protect in the Pillory. But this is a protection that may impede further develop, a protection that does not allow any scape from this group identity. As Kaplinsky says: "to belong implies a boundary and while a boundary provides a sense of containment, it can also be an area of intercourse, or a point to be broken through – or out of " - in order to 'become' and 'individuate'". (Kaplinsky 2009, p.63)

Although the trauma of kidnapping and forced subordination was not directly experienced by the subjects of this study, the memory of slavery seems to forge a collective identity even if not felt by everyone in this community. We may even wonder if the name "pillory" somehow has an unconscious effect on the population "obliging" them to repeat the collective memories as a contemporary experience. As we saw it, the place where it stood for centuries has been replaced by fountains, statues and musical centers, but its name certainly lets no-one forget the slavery that was practiced there and seems to be perpetuated as a cultural complex centered on a collective trauma.

We know that when trauma fails to be integrated into the totality of a person's life experience, the victim remains fixated on the trauma. Disruption or loss of social support is associated with inability to overcome the effects of psychological trauma. Lack of support may leave enduring marks on subsequent adjustment and functioning. Freud (1893) described a compulsion to repeat the trauma as an attempt of the organism to drain this excess of energy. He thought that by redoing and repeating the trauma the victims attempted to change a passive stance to one of active coping. Wouldn't be the case of the abandoned children on the streets? Wouldn't that explain the feeling of victimization of some habitants?

Conclusion

The ways in which the collective memory and the representation of a shared past are present in Pillory, through painting and music, do not amount to an elaboration or transformation of the trauma, but may raise two hypotheses: they could be expressing defenses that might help this group's spirit to survive, or else reveal a split between the collective psyche, a trauma and a cultural complex. Perhaps both are valid.

If trauma links past to present through representations and imagination, then what we witnessed as the representation of slavery, may indicate that this trauma is acting out in the present in the form of repeated and compulsive behaviors of unconscious submission and low-esteem, which may explain the critical socio-cultural situation of African descendants in most parts of Brazil. The few historical black personages, such as the slave Anastácia and others that belong to the heroic struggle for liberty, were not incorporated in the collective consciousness and remains hidden at the back of a small cemetery, for example. Rarely mentioned, portrayed or sang by their descendants, they are not used as examples for pride or self-esteem. The cultural richness and capacity of resilience of Afro-descendants, and the contribution that their ancestors made to the development of the nation, remain unconscious. The ideas of dominion, control and power are still deposited in whites, thus provoking a defensive splitting. According to Young-Eisendrath (1987:41), in this case two conditions may be present: anxiety (or fear) - when the Other is experienced as powerfully evil - or envy - when the Other is experienced as powerfully good, but holds the power and "the goodies" for itself. As she points out: "racism is a psychological complex organized around the archetype of opposites, the splitting of experience into Good and Bad, White and Black, Self and Other". One of the consequences of this scission is explicit in projections on the "Negro's body" (Young-Eisendrath 1987:41) Prostitution and exploitation of the body, especially the bodies of mulatta women sold as merchandise, and of the black male body as being strong and sensual, is based on the stereotype that blacks have better "physical" attributes, as if they were "closer to nature" and therefore endowed with an especially attractive sexuality and exceptional strength. This stereotype is clearly assumed by the population observed, who use their body and corporal art as the principal vehicles of their culture. The same fact we had observed in our studies with teenagers when the girls see the possibility of professional success though body exposure. Paula and Walter Boechat made a similar observation: "the idea of the inferiority of non-white groups still remain in the cultural unconscious (this is) the idea that blacks may come to a social realization only in sports or in music, not though an academic profession". (Boechat, W and Boechat, P. 2009, p.112)

On the other hand we may understand some behaviors observed in the Pillory, as defensive forms of behavior, maneuvers to seduce and deceive the powerful, and are far from expressing the true feelings of this population. They may even be considered as a form of resilience and capacity for survival of these people who still hesitate to assume their full freedom. A good example is a scene observed in a restaurant in the Pillory, with the gentle, smiling response of the (black) waitress to the aggressive (white) customer who complained about the slowness of service: "Calm down there, my king, what's the hurry, your food's on its way".

So, the more we study this phenomenon, the more complex it becomes. What is evident is that the silence and lack of studies on the matter have contributed to preserving stereotypes that are emotionally-charged beliefs based on cultural complexes that interfere with seeing people more precisely and empathically. Probably these stereotypes belong to all Brazilians, which make it difficult for a large part of this population to develop, both emotionally and in socio-economic terms.

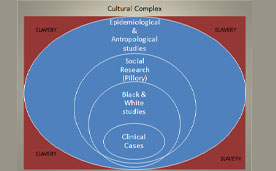

So we might say that the anthropological, historical and social studies, the epidemiological data, the black and white comparative studies allow us to affirm that there is strong evidence of a cultural complex due to slavery trauma in the observed population. (Figure 6) And we might also say that in order to have a healthier country, the new generation needs to interpret and come to terms with their collective traumatic past and their relationship to the past. And to achieve this, it is necessary to research the origins, to heal the trauma and to restore the dignity of the black heritage. It is important to notice that the question of trauma brought on by slavery has formed a complex that reaches the Brazilian culture as a whole, and not just African descendants. This complex probably feeds the inferiority complex pointed out in other studies, which is considered the psychological base for the tolerance towards political corruption in the country (Ramos 2004). Once all Brazilians are in some way affected by these complexes in his or her upbringing, now identified as "superior" and now "inferior", the national identity and the possibility of building a healthier and fairer nation becomes endangered, perpetuating countless sinister projections independent of skin color and disconnected from reality, but imprisoned in a shameful and tragic history. In this case we are all "victims", and only the painful awareness of the "nation's blackness" will be able to restore the value of the African heritage in forming a national identity. By the way, there is no such term as "Afro–Brazilian", "African-Brazilian" or "African descendent". These terms have been used here just for the purpose of differentiation. We all call ourselves, simply, "Brazilians", which probably indicates that a part of the social substratum that forms the national identity remains intact.

REFERENCES

Avanci, J et al. (2007) Adaptação transcultural de escala de autoestima para adolescentes.

Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica 20 (3):1-13.

Barton, C. E. (2001) Sites of memory: perspectives on architecture and race, New York:

Princeton Architecture Press.

Boechat,W and Boechat, P. (2009) Race, racism and inter-racialism in Brazil: clinical and

cultural perspectives in Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Congress for

Analytical Psychology. Daimon. Verlag. Einsiedeln, Switzerland.

Cerqueira, N. (ed.) (1994) Pelourinho, a grandeza restaurada, Salvador: Fundação

Cultural do Estado da Bahia.

Elkins,S.M.(1968) Slavery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Eltis, D. (2003) Migração e estratégia na história global. In Florentino, M. and Machado

C. (ed.), Ensaios sobre a escravidão, Belo Horizonte: Editora IFMG.

Eyerman, R. (2001) Cultural Trauma: Slavery and the Formation of African American

Identity, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Furtado, C. (2000) Formação Econômica do Brasil, São Paulo: Publifolha.

Freud, S. (1893) On the Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena. Int. J. Psycho-

Anal., 37 (1), 8-13. (Translation by James Strachey, 1956)

Hale, E.G (1998) Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1880-

1940, New York: Pantheon Books.

Henriques, R. (2001) Desigualdade racial no Brasil: evolução das condições de vida na

década de 90. Rio de Janeiro: Ipea (texto para discussão nº 807). Retrieved:

www.ipea.gov.br.

Hoffmann, R. (2001) "Distribuição da renda no Brasil: poucos com muito e muitos com

muito pouco", in: Dowbor L, Kilsztajn S. (org) Economia social no Brasil. São Paulo:

Senasc.Ibge.

Kaplinsky, C. (2009) Shifting shadows: shaping dynamics in the cultural unconscious

in Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Congress for Analytical Psychology.

Daimon. Verlag. Einsiedeln, Switzerland.

Kilsztajn, S. et al. (2008) Race, Equality and Income Distribution in Brazil, retrieved

from http:// www.abep.nepo.unicamp.br, accessed on 2008, June 10.

Lima, M. E. and Vala, J. Social success, whitening and racism. Psic.: Teor. e Pesq. 2004,

vol.20, n.1, pp. 11-19.

Miranda, L. B. & Santos, M. A. (2002) Pelourinho: desenvolvimento socioeconômico.

Salvador: Secretaria da Cultura e Turismo.

Pinho, P. (2004) Reinvenções da África na Bahia, São Paulo: Anna Blume Editora.

Ramos, Denise G. (2004) "Corruption. A symptom of a cultural complex in Brazil?" in

Singer,T. and Gimbles,S. The Cultural Complex -contemporary Jungian perspectives

on psyche and society. Hove and New York: Brunner-Routledge.

________________ (2009) The influence of ancestrally and skin color in self esteem and

identity: a comparative study between graduated students from São Paulo and

Salvador. Unpublished research. PUCSP.

Ramos, D. et al. (2010) Identity formation and feelings of self-esteem: a comparative study between black and white students. Unpublished research. PUCSP.

Rocha, C. (1994) Roteiro do Pelourinho, Salvador: Oficina do Livro.

Singer,T. and Gimbles,S. (2004) The Cultural Complex -contemporary Jungian

perspectives on psyche and society, Hove and New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Young-Eisendrath, P. (1987) "The absence of black Americans as Jungian Analysts",

Quadrant, 20(2).

Figure 1

Photo by the author, 2009

Figure 2

The owner's daughter by Adriano Luiz Gonçalves ( Salvador, 2009)

Figure 3

Food for birds by Raimundo Bastos dos Santos (Salvador, 2009)

Figure 4

Orixá by Ricardo Miranda dos Santos (Salvador, 2009)

Figure 5

São Joaquim's street fair by José Maria de Souza (Salvador, 2009)

Figure 6

|